No country has been able to figure out and successfully implement a right-to-repair legislation, says the CEO and co-founder of iFixit. However, he says after a Presidential executive order and intense pressure from consumer advocates, the U.S. is in a strong position to cement right-to-repair legislation in the near future.

Last week, the Federal Trade Commission issued a policy statement committing to prioritizing aggressive action against manufacturers who impose unfair repair restrictions. The announcement came days after U.S. President Joe Biden signed an executive order that directed the FTC to do so.

In an interview, Kyle Wiens explained that the U.S. Congress has passed right-to-repair legislation, but it only pertains to the automotive industry.

"The only reason your local mechanic exists and can get information from Ford on how to fix cars is because of existing right to repair rules," he said. "(Other) legislation would make a huge difference (in a variety of industries) and that's what we need to level the playing field."

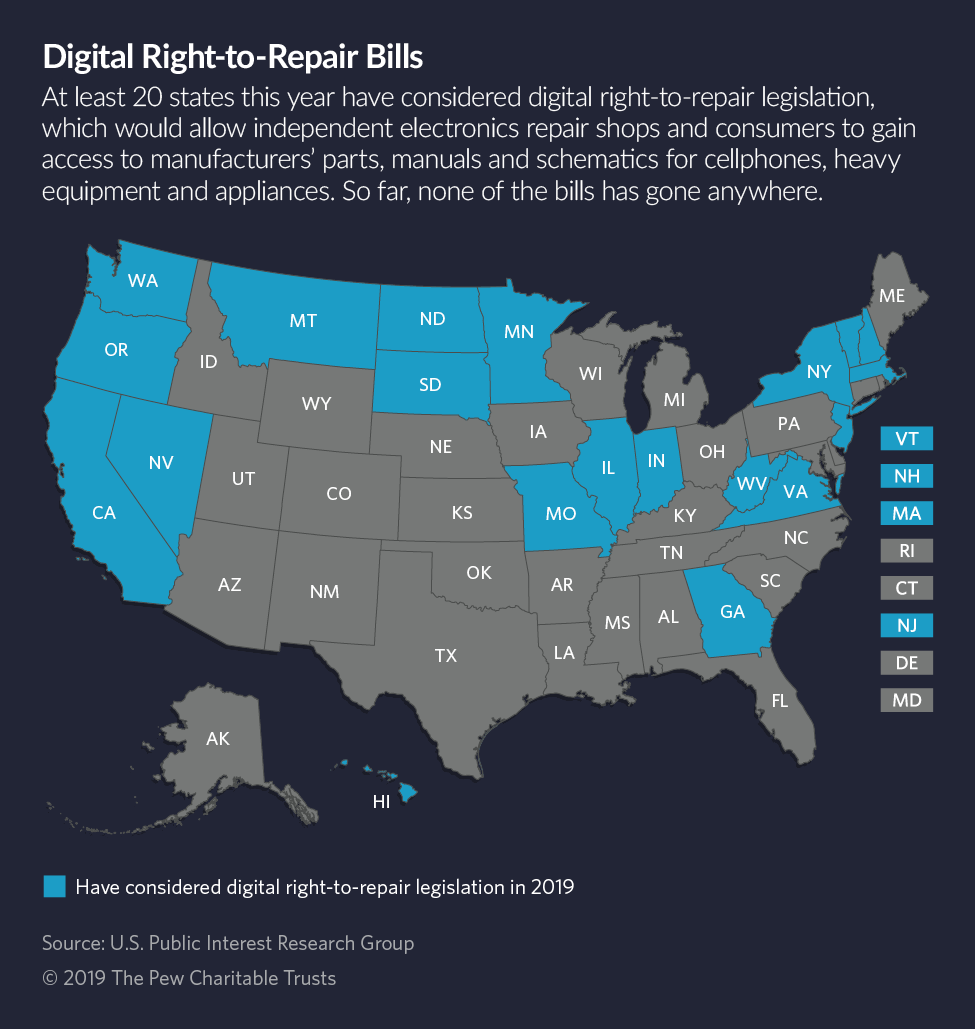

The goal now, he says, is that a new legislation will be one that extends to technology manufacturers part of a wide range of industries including banking, tech platforms, labor markets, internet service providers, and airlines. As of now, 27 states have considered some form of legislation this year, but what these states have considered doesn't mean it will get approved immediately and turned into law.

"This is a fight that has been breaking for a long time," he said. "Manufacturers are increasingly locking people out of their products. And I think this is a pivotal movement and where technology goes in the future. Either we step in now, we say things need to stay repairable, (or) manufacturers can use new techniques at their disposal to lock people out at all or lock them into their repair ecosystem."

The right-to-repair movement dates back to the '90s, but in 2012, Massachusetts passed a ballot initiative for cars that said if a consumer wanted to fix their own car or take it to a mechanic the manufacturer could not stop you. The manufacturer had to provide you with information, parts, and tools you needed to fix your car.

The proposed right-to-repair legislation that would extend to all technology companies refers to the ability to allow consumers to repair and modify their own technology by receiving the means to do so. This means that companies like Apple, Samsung, Microsoft, or other Big Tech companies would be required to make repair manuals available publicly and in some circumstances sell materials to fix products. A new law would then let you be able to fix the best Android devices easily.

France has a right-to-repair standard, but it's not good enough

Weins notes that the default now is the path that Apple has taken, which is to "totally lock people out," and other manufacturers are copying that method.

The problem is that no country as of now has been able to adopt adequate right-to-repair legislation, Weins says, adding that while France has developed a type of standard to help consumers, it's not good enough.

Currently, France is one of the only countries that requires companies like Apple, Samsung, Microsoft, and other device manufacturers to be more transparent and provide better long-term support for their products.

France's repairability rating law requires that companies self-evaluate and declare a score, which is monitored by France's regulator. The score is compiled by companies using "detailed spreadsheets" and covers five categories that are each worth 20%: documentation, disassembly, availability of spare parts, price of spare parts, and product-specific assets.

"What France is doing is really cool and they are leading the way," Kyle Wiens says.

"What France is doing is really cool and they are leading the way," Wiens said. "There has been a study that Samsung commissioned that found that 80% of consumers were willing to buy a device that had a higher score. So that is definitely moving the needle."

Carl Szabo, vice-president and general counsel of NetChoice, an industry group whose founders include Google, Facebook, and Amazon, agreed with Wiens in an interview that there isn't any country that has properly figured out right-to-repair.

"I think the reason you haven't seen other countries calling for it is it's not a big deal for them and/or they recognize the potential consumer harm," he said.

Lawmakers need to understand how right-to-repair could harm consumers

Szabo, who used to work for former Republican-led FTC Commissioner Orson Swindle, explained that while the right-to-repair initiative and potential legislation that would extend to other devices is important, lawmakers need to understand the harm that consumers could do to themselves if they try to fix their phones or have an unauthorized dealer do so.

"Let's say my dad's Samsung phone screen breaks and I go to the mall and I pay someone to fix the screen. A couple of weeks later the phone starts to glitch out. Do you blame the repair store? You could say that you'll never buy a Samsung device and it could have been no fault of Samsung's and could have been the repair store.

"(But) if it turns out it's a failure of the manufacturer, the manufacturer is going to have a pretty good defense by saying you can't prove it was my fault because they went to someone else and did this," he said.

Critics of right-to-repair say that companies are just going to deny more warranty claims because they can't prove the product wasn't meddled with.

He noted that mandated access to the supply chain is not the same discussion and that if a right-to-repair legislation is put forth then the discussion around the failure to repair something needs to be included.

Tim Bajarin, the chairman of Creative Strategies, adds to this discussion in an article in Forbes, noting that he is not opposed to the FTC "making it easier to repair smartphones or other complex tech devices."

"I am not sure it is wise to expand it to users themselves. Without clear-cut rules that define the responsibilities a do-it-yourself must adhere to, it has the potential for complications for the companies who make the products and those who try and fix their device themselves."

He writes that if someone tries to fix their own phone and it doesn't go well, the FTC needs to "spell out in detail" responses to specific questions: Who takes the responsibility to fix the device? What if it is damaged during the attempted repair? What responsibility should the device maker be charged with, if any? Will the FTC policy ruling over-ride any warranty policies a company may have in place?

How can manufacturers make up for a loss when unauthorized dealers fix products?

Another argument that many who do not agree with the right-to-repair legislation is that manufacturers make a loss by not having consumers go directly to them to repair their products, but Wiens said in this circumstance companies should sell their intellectual property.

"Make money by selling parts. Sell the tools and reap the benefits of increased customer goodwill," he said. "(For example), Samsung should be making parts and they need to make it available at very reasonable prices. That is part of the problem, some repair shops are able to get parts from Samsung, but the prices are so high that repairs are astronomical."

And while Samsung makes it difficult to repair some of these products, Wiens noted that the company's Galaxy Buds are a perfect example of a straightforward fix.

"Samsung's Galaxy Buds have a removable battery and (it's) very straightforward and easy to replace the battery and we're thrilled by that," he said. "It's a great design and it gets good reviews and people like it. It's comfortable and it's repairable. The AirPods get a zero out of 10, while the Buds get an eight out of 10."

And while Szabo believes the right-to-repair movement is important, mandating companies to release intellectual property doesn't "match the reality of the situation."

"(iFixit) is a fantastic website. I can go there right now and figure out exactly how to repair my Samsung device. The whole website is predicated on telling people who don't have access to those manuals how to fix their devices," he said. "So the argument that there's this information gap, I don't think matches reality, especially for consumer-sided devices because of websites like iFixit because of YouTube videos, because of Reddit."

Right-to-repair legislation needs to exist to level the playing field

Despite Szabo's reservations in making intellectual property public, Wiens still believes that in order for there to be a level playing field and that all shops can function fairly if information is made publicly.

"The situation we have right now is where there are some authorized jobs and everyone else is left in the dark. The point is a law would say, no you have to make it available and that everybody has access," he said. "The point of the law is to have a level playing field. That everyone has access to it whether they're certified or not."

Szabo disagrees and indicated that those unauthorized shops are trying to "get all the benefits of being an authorized repair shop without any of the labor or capital investment."

In January, Massachusetts updated its existing automotive right-to-repair legislation. While the FTC and the White House are determined to tackle the right-to-repair legislation, it is also drafted at the state level. Nothing can proceed until at least one state has passed a law that extends the right-to-repair legislation to all types of technology, or if the FTC tackles it first.

Post a Comment